For this week’s post, our class was assigned an online scavenger hunt. The items we had to search for, we were encouraged to not use our handy friend Google.

Below are the items we had to look up and the process I went through in finding them:

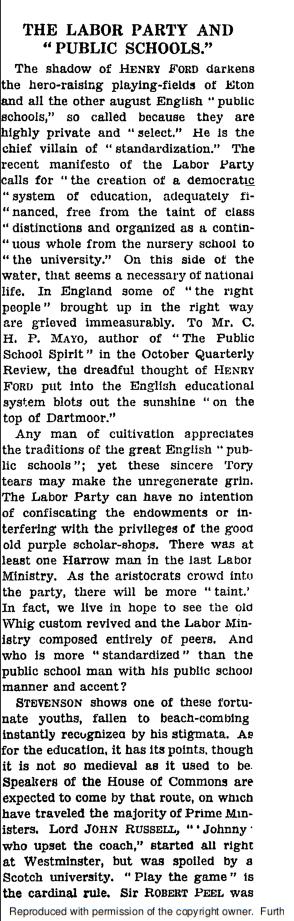

1. An op-ed on a labor dispute involving public school teachers from before 1970.

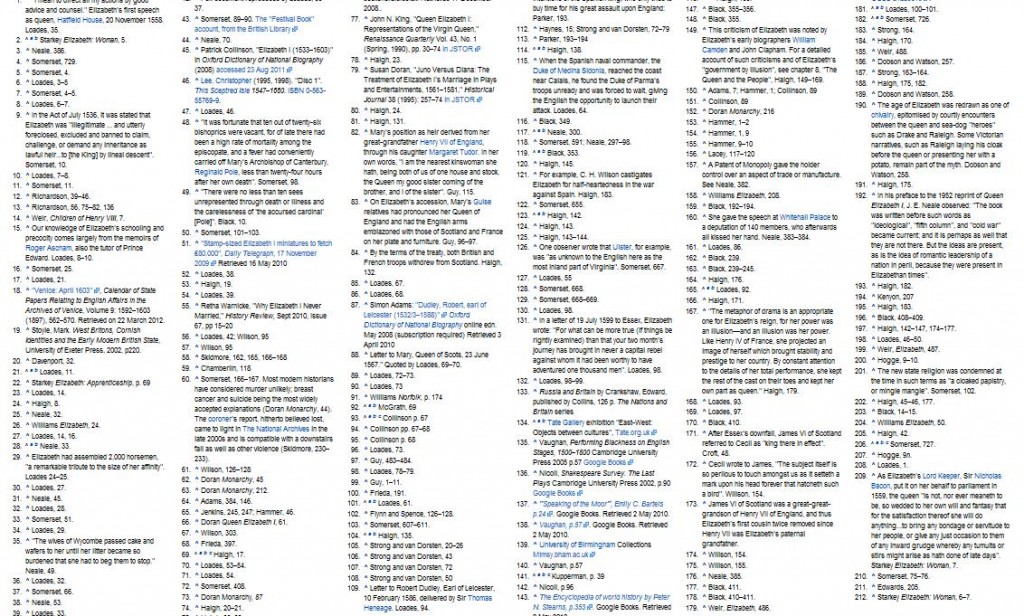

For this item, I simply went to the Pro-Quest database, which is accessible to GMU students. I went to the Historical newspapers section of Pro-Quest. I selected the “Advanced Search” section and typed in “labor AND public school.” I also selected the option to narrow down my search results, by selecting “before 1970” of any month and any day. I then went to the drop-down menu and selected only for editorial selections to be searched in. I knew I had to specifically look for a way to narrow down reports of labor disputes with public schools from what I was looking for, which were op-ed/editorial pieces.

I found a lot fewer results that matched with my search topic, meaning I had properly narrowed down my topic out of all of the information I had before. The first of which included a piece from the New York Times October 28 1928.

This is just one of two search results that appeared when I searched. Another included a similar piece from the Christian Science Monitor on November 1, 1927. Both dealt with issues going on in Great Britain.

Overall, this item I did not find hard to find.

2. The first documented use of solar power in the United States

This item was a little bit harder to find. I found a feature piece from the New York Times, however it dealt with solar power in Israel. However, I later realized the assignment asked for the United States. So I went further down my search results. I did the same process as I did with the Op-Ed piece, however I removed the date limitation.

I had to narrow down my search even more by only searching items before 1989, as anything before 1990 would be irrelevant as solar power started being used in the 1990’s. Then I had to narrow down my search even more by replacing the phrase, “Solar panel” with “Solar Photovoltaic power AND United States.” Solar Photovoltaic was being used in many of my search results, so I decided to only search items with this phrase instead.

What I ended up finding each time were reports of the first solar pond, but of the first use of solar energy. I then found that I wanted to change the date to be before 1982. As a result, my search was even more narrow to only 465 results. However, I’m still not sure if I ended up finding what I needed. Many reports discussed the first solar house, or the first use of commercialism solar power, not the first use of just ANY solar power within the United States.

So I failed by using my friend Google to help me find the timeline for the, “history of solar power.” It directed me to a timeline from the U.S. Department of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy. While I did not find the first account of solar power use in the United States, I was still able to find a reputable source of exactly what I was looking for.

What I found the problem with databases is that you have to know EXACTLY what you are looking for and EXACTLY how you are going to find it. In the past, I’ve had trouble finding sources on databases before because there is just so MUCH information, that it’s hard to find out exactly what you were looking for in the first place. However, with Google I only had to type in one thing and I instantly got what I was looking for. Initially, searching for something via Google doesn’t blind you from all of the search results you are inevitably going to get if one simply goes head first into a database expecting to find something.

3) The best resource for the history of California ballot initiatives, including voting data.

For this item I knew I needed to look somewhere else besides historical newspapers. I instead went to the the library set of databases and went to the letter “D” to find Data.gov from the United States Government website.

I wasn’t 100% sure what I was supposed to be looking for. So I typed in, “voting data for ballot initiatives in California,” and came to the University of California-Berkley’s library site. Detailed in it, it gave me a .pdf of the history of the voting initiatives in California. Within this, I found the date October 10th, 1911 for when, “the initiative process was established in California by a margin of 168,744 to 52,093 votes cast for Senate Constitutional Amendment (SCA) 22. S.”

Using that date, I decided to go to the Pro-Quest Historical newspaper data base to find a press clipping of this information to make sure that what I was getting was factual. I searched, “California AND voting initiative” narrowing down my search to only show results before 1912. I came up with 252 search results and a press clipping from the newspaper Outlook in American Periodicals from October 21, 1911 (.pdf).

What this exercise taught me is that Google is the first stepping stone. It’s really difficult to navigate around databases, particularly when you aren’t an expert on a topic. This is because you don’t know what you’re looking for or where to start. With the second item, I had a very difficult time trying to find the first use of solar power because it wasn’t called solar power to begin with. While Google isn’t the answer for everything, it’s a good first start to doing some small background research to make sure you know exactly what you are looking for.